Knowledge is power. Understanding who harms children, how bias shields some offenders, and how systems fail Survivors helps protect children—especia

Knowledge is power. Understanding who harms children, how bias shields some offenders, and how systems fail Survivors helps protect children—especially in communities often overlooked or harmed by systemic inequities.

1. Are perpetrators ever identifiable by race?

Yes—and but. Race shows up in official data, but data alone doesn’t tell the full story. Recognizing racial patterns must be balanced with the truth that abuse can—and does—happen in all racial and ethnic communities.

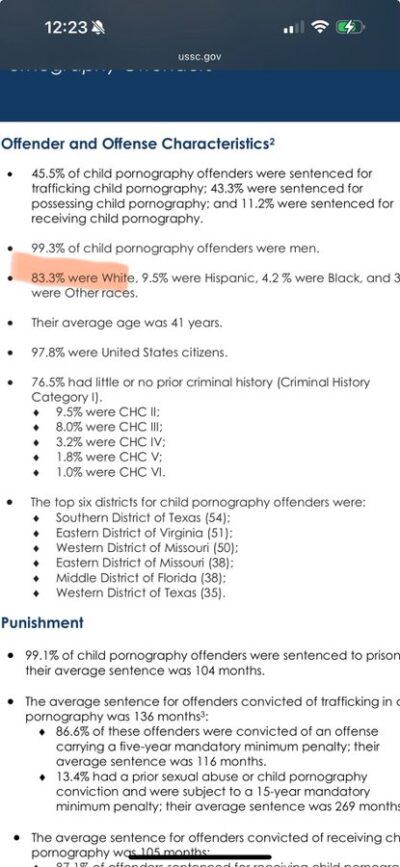

According to U.S. Sentencing Commission data (FY 2021), among convicted sexual abuse offenders:

~ 57.5% were identified as White

~ 16.1% as Black

~ 12.1% as Native American

~ 11.8% as Hispanic

~ 2.5% as other races U.S. Sentencing Commission

The same report noted that, in cases involving production of child pornography, 74.6% of offenders were White U.S. Sentencing Commission

In FY 2018, 75.1% of offenders in child pornography cases were also White U.S. Sentencing Commission

These statistics show that a large share of documented perpetrators are White, but that doesn’t mean children of other races are safer—or that perpetrators of color don’t exist.

2. How does systemic racism, bias, and prejudice protect certain perpetrators?

Abuse does not occur in a vacuum. Structural inequalities, institutional biases, and stereotypes can shield perpetrators and harm survivors—especially in Black, Indigenous, and communities of color.

Here’s how:

| Barrier / Bias | Impact on Survivors / Accountability | Example / Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Under-reporting or disbelief based on race | Children of color may be less believed, or their disclosures minimized. | Black girls are more likely to be stereotyped as “older,” “less innocent,” or “hypersexualized,” which can lead adults to dismiss their vulnerability. |

| Biases in child welfare or law enforcement response | Cases involving children of color may receive delayed or weaker responses. | Studies show Black and Latinx children are more often referred to child protective services for abuse, but also more likely to have their cases unsubstantiated or handled inequitably. ScienceDirect |

| Fear of being accused of racism | Some institutions avoid naming or investigating perpetrators of color, especially in high-profile cases. | In some cases, authorities avoid collecting or publicizing race/ethnicity data about offenders to avoid backlash or accusations of bias. |

| Resource disparities in marginalized communities | Survivors in under-resourced neighborhoods have fewer access to advocacy, legal support, or trauma-based care. | Systemic neglect means less monitoring, fewer trained professionals, and weaker institution accountability in marginalized areas. |

| Stereotypes that shield “respectable”-looking offenders | Offenders who appear “safe” (white, educated, religious, professional) may escape suspicion more easily. | Perpetrators from privileged backgrounds often exploit trust and authority; bias may lead institutions to doubt accusations against them. |

Because of these combined forces, perpetrators of color may be disproportionately invisible in the system—or survivors may be doubly traumatized by both abuse and institutional betrayal.

3. So, what does this mean for parents—especially parents of color?

Don’t rely solely on stereotypes. Predators don’t always look like “what we expect.”

Insist on equitable treatment. If your child discloses abuse, ensure law enforcement, child protective services, or medical systems respond without bias.

Advocate for data equity. Call for authorities to record race/ethnicity of offenders and publicly report disaggregated data—transparency strengthens accountability.

Partner with culturally competent support systems. Seek out therapists, advocates, or organizations that understand racial trauma and trust-building in marginalized communities.

4. Why emphasizing race and bias strengthens protection

Naming racial dimensions helps expose how some perpetrators escape scrutiny and how survivors of color may face added barriers.

It shifts the narrative: abuse is not just an individual act of evil, but often enabled by social and institutional injustice.

It empowers communities that are too often silenced or dismissed to speak up, demand change, and protect their children.

5. Revised “perpetrator types” chart, now with race-conscious framing

| Type of Perpetrator | Access & Tactics | Racial/Bias Risks to Watch | Notes for Parents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parents / caregivers | Hidden, private abuse; use of authority | Perpetrators may be protected by family reputation or institutional bias | Enforce transparency, monitor access, watch for secrecy |

| Extended family / community insiders | Leverage cultural respect, community ties | Sometimes shielded by community loyalty or silence | Ask hard questions, break silence, trust children’s voices |

| Trusted professionals / authority figures (teachers, clergy, coaches) | Exploit power and trust | Those viewed as “safe” due to appearance or status may evade suspicion | Demand accountability, reporting, and oversight |

| Online predatory adults | Grooming, manipulation via chat, social media | They may target children of all races, but also use racial dynamics (e.g. fetishization, racialized messaging) | Teach digital boundaries, safety skills, and know reporting channels |

| Peer perpetrators / minors | Pressure, coercion, underage sharing | Sometimes racial dynamics play (bullying, exclusion, power hierarchies) | Monitor peer groups, keep communication open, deconstruct shame |

6. Sample revised FAQ entry with race + bias language

Q: Can perpetrators be of any race? Do race or ethnicity matter?

A (revised): Yes—abusers exist in every racial, ethnic, and social group. Many documented offenders in the U.S. are identified as White, but that fact alone doesn’t guarantee greater risk or innocence in any racial group. Meanwhile, systemic racism, prejudice, and bias can allow some abusers—especially those of certain racial, social, or institutional privilege—to evade scrutiny or accountability.

That’s why it’s vital to talk openly about race, question bias in systems, and demand fair treatment for Survivors of all backgrounds.